CHRONICLING THE PLIGHT OF STREET KIDS

by

"Perhaps we cannot prevent this world from being a world in which children are tortured. But we can reduce the number of tortured children. And if you believers don't help us, who else in the world can help us do this." - Albert Camus

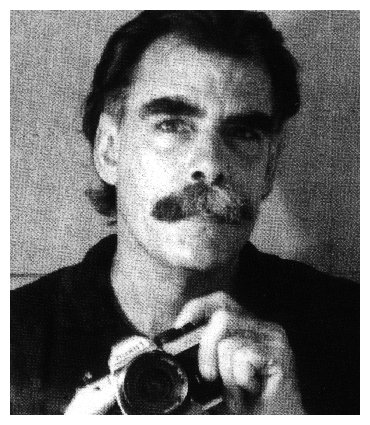

Mikel Flamm

I met with Mikel (pronounced Michael) Flamm in Swenson's at Times Square over a coffee to discuss his book Children of the Dust. The irony of meeting in Swenson's isn't lost on me. All these wonderful flavors of ice cream that the street children in Flamm's book can never even hope to taste. I had been impressed with Flamm ever since I first saw him cover the May Uprising. Showing a tremendous amount of courage he captured some of the most brutal images of that senseless slaughter, especially one particular shot of a slain demonstrator lying wrapped in a Thai flag near Democracy Monument.

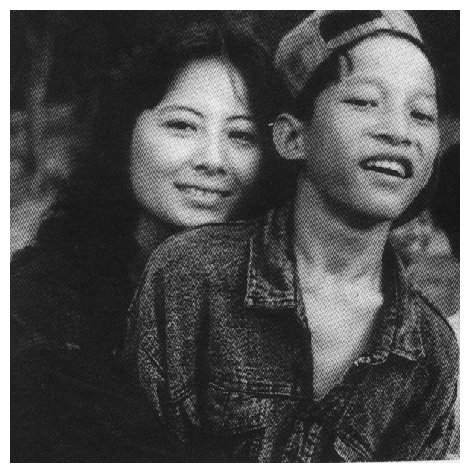

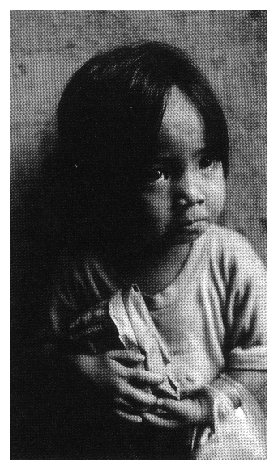

Ngo Kim Cuc with a streetchild in Danang

I wasn't able to meet Flamm's co-author Ngo Kim Cuc, so he filled me in. She comes from Hanoi and attended Hanoi University. Prior to joining World Vision in 1993 she worked with the UNDP in public works projects throughout Vietnam. Currently she is program officer for the World Vision street projects in Hanoi, Hue, Danang, and Ho Chi Minh City. She has two children: Hoang aged fifteen, and Duc aged nine. "She had a great relationship with the children on the streets," says Flamm, "So it was very easy getting information out of the kids. Even the abused children opened up to her as a mother image."

Flamm credits his father, Don, who is a freelance writer and a retired director of public affairs for Ford Aerospace, with sparking his interest in photography. "He used to work for Gardinia News years ago, and he was always taking pictures of us. So I've always been around it. My dad used to go down and cover the missile launches at Cape Canaveral in the '60s." (The elder Flamm, by the way, has done an exceptional job of editing Children of the Dust.)

"I attended photo school in junior college in 1969. I got my first real taste of photojournalism covering an anti-Vietnam War protest at Fullerton State University in 1970. It was a demonstration that turned into a riot. After that I was hooked."

Flamm then attended the Art Center for College for Design in 1976. After graduating he worked as commercial photographer specializing in fashion shoots. He first came to Thailand back in 1987 on a holiday with his brother. Back in California he read a story about the refugee camps in Aranyaprathet, and in 1988 he came back to photograph and write about the conditions of the refugees along the Thai-Cambodian border. He came back again in 1989, and in 1990 he moved here for good.

Mikel has worked for the United Nations, Save the Children and various publications as both a writer and photographer. He started working as a freelancer for World Vision in Bangkok in October of 1993. He then went on assignment to Vietnam in December which is where he first met Cuc. The says the idea for the book came about in early '94 when Ngo Kim Cuc and her boss Michael Hegenauer decided to do a book on the case history studies of children. The funding from World Vision came through in June of 95 when Flamm made the first of his two trips to Vietnam to gather information and take pictures for the World Vision project.

In describing World Vision he says, "It is an agency concerned with area development and sponsoring children. It's head office is in Monrovia, California and they are active in over one hundred countries concentrating on both the plight of the children and the communities they live in. They will select a large area and help set up projects in agriculture, sanitation, health, building schools etc."

When asked how chronicling all the suffered affected him, Flamm responds by saying, "We were both affected by the plight of the children but the seriousness of the problem touched her in a deeper way. Being a mother, she was very upset to see the children fend for themselves. As she spoke with the children I could see the strain upon her. I stayed with her during most of the interviews. Since all of the conversations were in Vietnamese, she would translate the children's stories into English for me.

Asked how the Vietnamese government dealt with the making of the book, Flamm says, "They really didn't want people (especially foreigners) to see the problems of the street kids and the delinquents. We had a good relationship with the authorities though, and we included interviews with them. Since it is a very touchy subject we didn't try to hide anything. They knew what we were doing all the time, and we let them know what are intentions were as well. We wanted to do this in a way so as not to point a finger at the government and say `Why aren't you doing something about this?' but rather to say this is what needs to be done to give these kids a better chance in life.

In describing the making of the book Flamm says, "The Vietnamese are very curious, especially when a foreigner is involved. We drew a lot of attention very quickly on the streets. When we would choose a child to speak with we would soon be surrounded by people who would just stand around and listen. Consequently, we often had to arrange our interviews in secluded spots, or noodle shops.

"Since we spent most of our time with the interviews I didn't get to concentrate on the photos as much as I would have liked to. Many of the photographs in the book were actually taken on previous trips to Vietnam in 1994. All total, we spent two months conducting the interviews and photographing the children. Then we worked on the stories. I'd do some writing in Bangkok while she worked on the project in Vietnam. Then we'd send information back and forth until we had a workable final draft. My father edited the final draft after it had been submitted to the Vietnamese Government in Hanoi for approval. They made a few minor changes before it went to print."

When I broach the subject of how and when aid should be given, Flamm says, "Aid has to be given in a way that is not a hand-out. In the late '80s and early '90s the Cambodian refugees on the Thai border were given everything - their rice, vegetables etc. without any work. Some of them lived like that for ten years. So when they finally went back to Cambodia they had a hard time working. World Vision has a project called for `Food for Work' where people do a project and in exchange for their work they are given food. Even the kids get involved in the project."

One of the many publications Flamm has written for is the Asian Defense Journal. When told he doesn't look like the military type he says," I like going out with the military on maneuvers but I'm not pro-military. Most journalists aren't especially after you see what all that stuff does to people."

Flamm cites Larry Burrows, Philip Jones Griffith and Robert Capa (aka Endro Erro Friedmann) as some of the photographers he most admires. "Capa was the ultimate war photographer. He was the one who said `If your pictures aren't good enough, you're not close enough.' He also likes the work of Van Bao, an North Vietnamese photographer who took some of the more memorable shots of the downed American airmen being captured during the Vietnam War. Of his contemporaries, Flamm admires Philip Blenkinsop for his use of black and white shots. "It's a dying art, but the images are much more powerful."

In the book's introduction, Vu Ngoc Binh the National Program Officer for Children in Especially Difficult Circumstances for UNICEF in Hanoi writes, "The street children phenomenon is a product of urbanization, poverty and a lack of alternative. For some, the streets are a permanent escape from broken families or domestic violence, while for others the street life is a means of supplementing income, of passing time and having fun, or of temporarily escaping from overcrowded conditions at home. In addition, unequal distribution of resources, limited economic opportunities and the breakdown of traditional family values and community structures deny millions of children the care and support they need for wholesome growth and development. Driven to the streets for survival, these children are rendered exposed to exploitation and constant risks. These children are a vulnerable group of children who are victims of economic, physical, and sexual exploitation and abuse, often in special need of three things: protection from dangers, access to services, and opportunities for personal growth and development. They need to grow as human beings with the love, care ad support that will ensure their physical, mental, emotional, social, and spiritual development. They need a support system that will help them acquire values and skills for their integration into the mainstream of society.

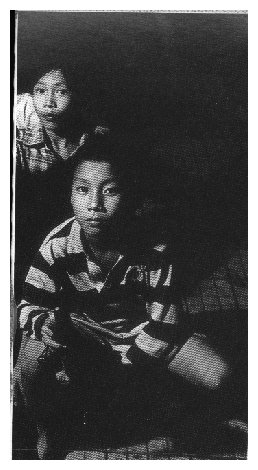

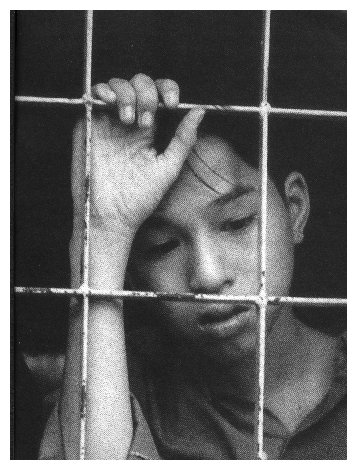

Trying to explain the plight of the street kids, and to give their problems some background, the authors note, "The majority of children we interviewed for this book conveyed that the two main reasons they left home were the breakup of their family and extreme poverty. If the parents did divorce or separate, each spouse frequently remarried soon after. The children commonly expressed they had great difficulty in relating to their step-parent. Abuse and neglect became commonplace, especially in situations where there were financial problems. At times the children felt that they were the main source of the family's problems and poverty. They felt unwanted, unloved and confused. With few options, they left home and took to the streets for answers.

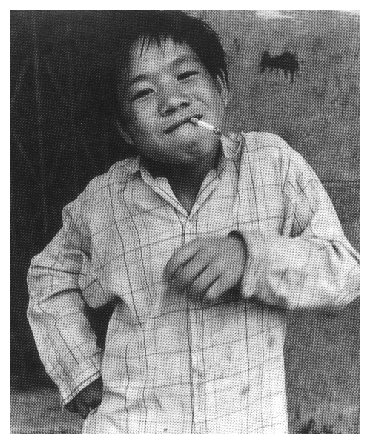

"Once on the streets, the children explained that they quickly had to adjust to their new surroundings. They expressed their fear and uncertainty as they learned how to adjust to their new life. With little or no belongings other than the clothes on their backs, the children soon learned that they were "prey" to other more savvy children, who often stole what little money or belongings they owned. If they resisted, they were often beaten. As a result, they learned to struggle on a daily basis in order to survive. This is a high price to pay for ten-twelve year old children, as they take a step into a world where childhood seemingly ceases to exist.

"Street children are commonly found in parks, plazas, churches, bus and railway stations, or any other public place where they can make money, or just "hang out." They are often associated with gangs, though some operate alone.

If they are a member of a gang, which may number from three on up to seven other boys, there is often one older boy who is the leader. He may be sixteen or seventeen years old, whereas the others are usually less than fourteen years of age. He teaches them to beg, steal or scavenge, and how to move from place to place to attract as little attention as possible. As the leader, he takes control of the money the others make, giving back a portion, but keeping the majority for himself. He is also the protector and provider of the group. If the police put pressure on his gang, he will pay off the law officials and request them to move to another gang's territory. If any of his members are arrested for stealing or for other petty crimes, he often helps to arrange for their release. When gang members become sick, he cares for them until they regain their health.

"Street children basically belong to three groups: Group 1-Children who have no fixed accommodation, family or guardian. They either have left their family environment willingly or were forced to. They sleep on the street, or occasionally in shelters, earning money by shining shoes, begging, stealing or scavenging, selling lottery tickets, cigarettes, or newspapers, and occasionally prostituting themselves, often to foreign tourists. Group 2-Children who sleep on the street with their family or guardian, begging, and scavenging, with their parents, brothers and sisters. And Group 3-Children who have a family, but wander the streets during the day, usually returning home at night, often becoming involved with gangs and petty gangs."

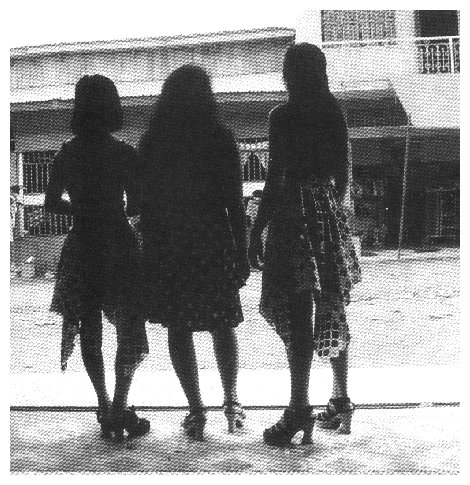

The last section of the book deals with children in the commercial sex industry and child trafficking. The authors who were originally only going to focus on street children in Vietnam decided to take a trip to Phnom Penh's notorious Svay Pak (The Street of Little Flowers) to chronicle the large number of Vietnamese girls being trafficked from Vietnam to Cambodia. In this part of the book Cuc and Flamm note, "The exploitation of children for sexual purposes in Asian countries is a highly organized and profitable business which continues to escalate at unparalleled proportions. In recent years the average age group of these exploited children has drastically dropped to fifteen years or younger, even to the point where twelve-thirteen year holds are often found in brothels. The majority of these children have been tricked and deceived, often by friends, relatives and parents and sold to middlemen, pimps or mamasans, who bind them to brothel contracts for periods ranging from six months to a year or more."

This is a good book. It is a worthwhile book and a much needed book. It deals with reality, the reality that street kids have to deal with day in, and day out. In their general background the authors include the highlights of the Convention on Children's Rights. It is tragic that some few of the articles in that charter which are meant to protect the young do anything to safeguard the lives of street children.

Children of the Dust is one of those books whereby after reading about the suffering and agony that these children endure you want to rush out and try to do something to help alleviate some of their pain. And you should, we all should. We all take for granted what we have, and seldom realize how difficult life is for the unfortunate and the under-privileged. And the next time you see a street kid think about the reasons why they are where they are.

If you want to help World Vision

you can contact them in Bangkok at 381-8860,

or

Mikel Flamm at

Miami Mansion

1629/7 New Phetchburi Road

Bangkok

10310

Tel 255-1010

Mobile 01-6579722.

-

email: mikels@loxinfo.co.th

website: www.mikelflamm.homestead.com

Children of the Dust is available at Asia and DK Books)

Finis

| Page Head | Home Page |