by

|

|

Keith Johnston's story is different. We should stay away from that oft overused "unique" but in truth that's what his life has been. The native of London, Ontario, has been roaming the world since he was very young age and shows no signs of letting up. |

The travel bug was nurtured in

Keith early on by his father, Douglas, a noted professor of environmental,

maritime and Asian law who taught all over North America and who took his wife

Judith, and children, Keith, Murray and Caroline with him as he went from the

University of Western Ontario to Louisiana State University to Yale, then

Harvard, the University of Toronto before somewhat settling down in Halifax,

Nova Scotia, and teaching at Dalhousie University. The senior Johnstons also

took the kids traveling with them whenever they could so Keith caught the travel

bug very early on.

In 1984, Keith graduated with a

Bachelor's of Science Honours Degree in Geology from Dalhousie but upon

graduating he realized that he didn't want to be confined to the insular

pursuits that geology offered. An opportunity arose, however, to help a Ph.D.

student do field work in Morocco and Keith jumped at it. He backpacked around

Europe for six months after his time in North Africa and says, "I loved it,

the sense of freedom, the sense of exploration," he says. "It totally

changed my life. I almost didn't come back."

But he did and in the fall of

1985, he returned to Canada and attended Queen's University where got his

Masters Degree in Business Administration. The summer in-between the two year

course he and three classmates thought up a project which sent them to Germany

where they did a study of the German steel industry and interviewed German steel

giants like Krupp and Thyssen. They were sponsored by Atlas, a Canadian company

who was trying to penetrate the German stainless steel market.

But he did and in the fall of

1985, he returned to Canada and attended Queen's University where got his

Masters Degree in Business Administration. The summer in-between the two year

course he and three classmates thought up a project which sent them to Germany

where they did a study of the German steel industry and interviewed German steel

giants like Krupp and Thyssen. They were sponsored by Atlas, a Canadian company

who was trying to penetrate the German stainless steel market.

"And then, of course, I

stayed in Europe for a while after the project," Keith says. "I went

down to France and hung out on the Riviera. I then started to form a pattern of

using every angle I could on a trip to see a new place in the world. I hung out

in cafes and did a lot of walking and I tried to get a sense of a place and a

sense of how people lived."

When Keith graduated from

Queen's he utilized the school placement program to get a job marketing zinc

metal in Toronto with Noranda, the mining and smelting company. He stayed in

that position for two-and-a-half years before being switched to a job marketing

sulphuric acid. It was a bit of a boring commodity he acknowledges but he did

enjoy the chance to produce a marketing video and design a brochure.

"Marketing sulfuric acid was a highly logistics dependent operation.

Noranda's copper, lead and zinc smelters produce about two million tons of

by-product acid annually by capturing the SO2 emissions from their smelting

processes. It's really more of a problem to get rid of than anything else, as

you can't store it indefinitely. End-users are companies in the fertilizer,

petrochemical, mining, pulp and paper, aluminum and orange juice

industries."

Keith worked for Noranda for

eight years, and his third job with them was buying copper concentrate, the

ultimate end-product that most copper mines produce. "Noranda is a large

net smelter," he says, "meaning its copper smelting capacity is much

greater than its mining capacity. So, it is a large importer and consumer of

other miners' concentrates.

"There is an active

international trade in copper concentrates and concentrates of other base

metals, and they are shipped in vessels, 5 to 10,000 tons a time, from

practically anywhere in the world to practically anywhere else in the world.

This is because there are many smelters that don't have enough, or any of their

own or other domestic mine production, so they must rely entirely, or partly, on

the purchase of imports for their feed, and because there are many miners that

are too small to justify building their own smelters. Mines obviously have to be

located where the deposits are, but you can build a smelter anywhere, and quite

often it makes more sense to build a smelter closer to the marketplace for the

refined metal than to the mine.

"In this field, I had

finally found something I really enjoyed. It was much more challenging than

marketing zinc or sulfuric acid. It's a very technically oriented business

because every mine produces a slightly different quality and every smelter has

different quality needs and desires. Concentrate markets don't really operate

fully as commodity markets the way metals markets do, because of these quality

differences. Dealing with concentrates is a more analytical pursuit, and I

realized this was something I could sink my teeth into and do for a long

time."

Keith, however, started to grow

disillusioned with Noranda. As it became more and more of a corporate entity, it

became less of a comfortable place for him. Even though he loved his job, he

started to hate his work environment. So he started looking for a new job as a

trader.

"As a buyer of concentrates

for Noranda, I was dealing with miners constantly, but also with traders of

concentrates. Because supply and logistical disruptions are common we had to

employ a strategy of diversified supply sources. Traders essentially provide a

role of globally managing the marginal units of production around the world.

They are willing to take the supply risks that the miners and smelters cannot

because they have a global reach. So they do provide a very valuable role.

"I thought that the traders

I had met were a very impressive group of people with a wealth of knowledge who

were working in a very demanding and intense profession which required a lot of

traveling." The problem was they belonged to a very small clique, which was

very difficult to break into it. An opportunity finally arose for Keith with

Sogem, a branch of the big Belgian smelting company Union Miniere. UM is a

smelter of zinc, copper, lead, precious metals and numerous associated metals

and minerals as well as a downstream metals processor.

Keith was flown to Brussels and

New York for interviews before eventually being hired in November of 96 (he

moved to Bangkok in February of 97.) Keith was initially supposed to work for

Sogem managing a purchasing agency they had with a

copper smelter project in Thailand called Thai Copper but it didn't pan

out. Just before the financial crisis kicked in, Union Miniere decide to give up

its ten percent stake in Thai Copper and the agency was cancelled. But the

company decided it needed somebody in Asia to exclusively trade concentrates

because it had not been well represented here in the past and it recognized that

Asia would be an increasingly important global trade zone. It made sense to have

a greater presence here, and Bangkok was a logical choice because it is a hub

for this region.

Keith's responsibilities today

are to trade copper, lead and zinc concentrates and he is responsible for a

region stretching from Japan to India to Australia and everywhere else in

between. As a trader, he and his colleagues around the world, take the

concentrate from the miner, arrange the ocean freight, have it loaded at the

port, and unloaded at the receiving port. From there, the smelter would then

manage the in-land freight and ultimately refine the concentrates to pure metal.

The London Metals Exchange, a

futures market, is used to hedge the pricing differences between the purchase

and the sales side of the trade.

"Most of what I do is

information gathering and analysis in an effort to predict what is going to

happen in the market so that we can develop trading opportunities. Because

smelting processes and conditions differ somewhat, each smelter's sensitivity to

impurities may be unique, so in order to properly assess the impact of a change

in supply and demand I have to know each smelter individually. This requires a

lot of traveling."

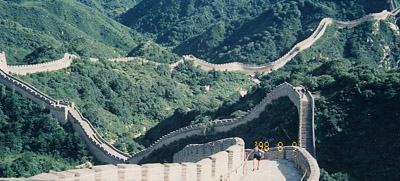

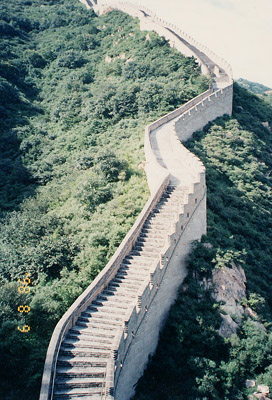

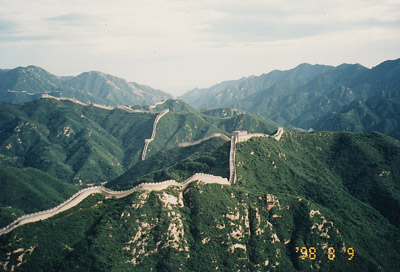

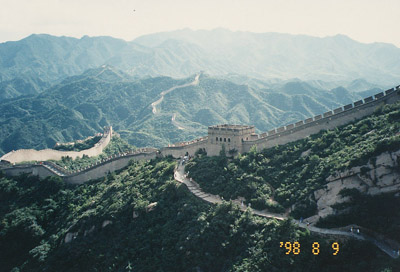

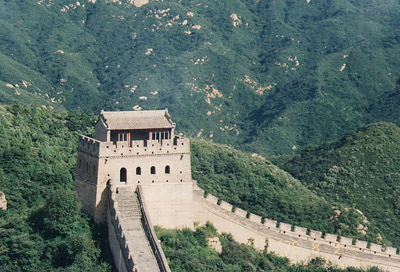

Mr Johnston certainly gets

around. In the past year alone, he went to China five times, Japan three times,

India twice, South Korea twice, Australia twice and the Philippines twice.

Keith says his job is perfect

for him. "It's intellectually challenging and I love the pace of it. But

one of the big reasons why I wanted this job was because of the travel involved

and I've always known I wanted to live the life of an ex-pat. Nothing satisfies

me more than going to some place I haven't been to before. I don't even care if

it's a nice place and or if there is anything to do there. I have an obsessive

need just to experience a place I haven't been to before. And I get some sort of

appreciation out of everywhere I go."

Commenting on Thailand, Keith

says the beauty of this country is four-fold, "What makes living here

attractive is the cost-of-living, the golf, the beauty of the long weekend as

there are just so many things to do that are only a short flight or drive away,

and of course the people and the culture."

Keith probably best sums up his

life when he says, "I came to the rather obvious conclusion long ago that

one's life is, or at least should be, a continuous process of experiences and

reflections. Somewhere along the road, I began to realize that the majority of

experiences that were providing the most enlightening reflections were taking

place in unfamiliar settings."

For more information contact

Keith c/o:

Tel (office): (662) 678-4681

Fax: (662) 678-4682

Mobile: (661) 815-6630

E-mail: keithj@loxinfo.co.th

Photographs by Keith Johnston

Finis